Author Archives: Amanda Schooley

Amanda’s Reading Questions for April 7th

- We once again see peer-pressure patriotism throughout this text, which is best highlighted at the beginning of the story by the collectors trying to goad Miranda into “doing her bit” by buying Liberty Bonds she can’t afford, and we see later on that they had also approached her coworker, Townie, as well. How does Porter’s approach to this subject differ from other displays of homefront patriotism that’s been portrayed in other works we’ve read so far, such as in All Quiet or in Smith? Consider that this is a piece following not a soldier or a nurse, but a female journalist who still lives a relatively normal, if crummy, life—far away from the trenches. Consider, as well, the genders of the two parties involved in the exchange; is their attitude and conduct towards her reliant on their gender, social status, occupation, etc. and if so, how? Do these aspects pop up anywhere else throughout the text, and how does this impact the setting over the backdrop of the war? What does the response/attitude of Miranda and other characters regarding this patriotism do to reinforce the larger societal mindset prevalent of home effort during the time?

- While this story is primarily told from a third-person limited perspective, there are times in which Porter abruptly switches the tense style to a first-person perspective, best exemplified on pp. 281-2, 283, and 288, sometimes shifting in the same paragraph. Why do you think Porter chose to write this way, outside of mere authorial intrusion? How are these specific moments significant? Are these passages more or less impactful when told from this perspective compared to Miranda’s third-person POV, or about the same? How does this story benefit from being told primarily in third-person limited?

- What is the significance of the title, Pale Horse, Pale Rider? Are there any symbolic or religious references you can find throughout the text we’ve read so far to explain why Porter chose this specific title? What do you think the dream sequence Miranda has with the horses at the beginning represents, and can we draw connections between the two—if so, how? How could this be connected to the character of Miranda, her relationships, and her situation?

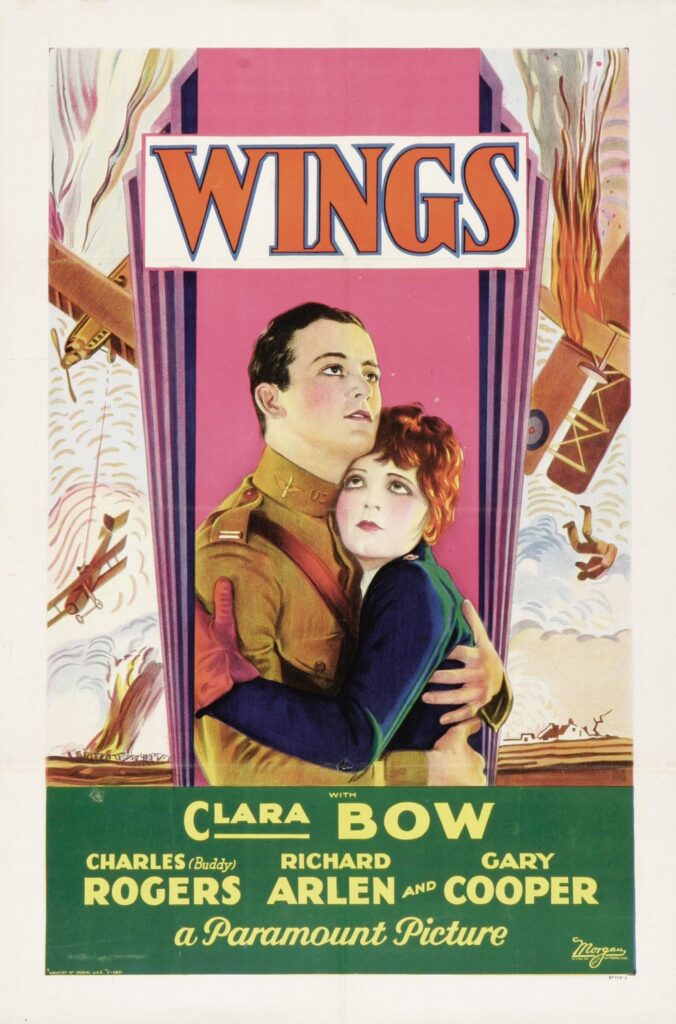

Amanda Schooley’s Review of Wings (1929)

Filmed in the span of just nine months, Wings is a 1927 American film (although it wasn’t actually released in the U.S. until 1929), directed by former WWI aviator, William A. Wellman, and starring Richard Arlen (also a former aviator in the War), Charles Rogers, and Clara Bow—Paramount’s bona fide ‘IT Girl’ and star with a big, glittery capital ‘S’.

The film is a romantic war drama, telling the story of two men: Jack Powell (Rogers) and David Armstrong (Arlen). Both men are from notably different walks of life: Jack is a middle class idealist with a dream of flying, while David is the son of the richest family in town and seems far more down to earth—really, the only thing the boys have in common outside of their decision to enlist in the War is their rivalry for the affections of the beautiful city girl, Sylvia Lewis (Jobyna Ralston). Meanwhile, Jack is painfully oblivious to the affections thrown his way by his friend and literal girl next door, spunky and doe-eyed Mary Preston (Bow). As 1917 closes in, both Jack and David enlist in the army to become aviator pilots and are billeted together and, following the sudden death of their tentmate and having undergone intense military training together, the two’s rivalry fizzles out into the gritty but affectionate friendship that sometimes borders on intimate as the war drags on, a relationship which feels all too familiar and tragic in this class. Meanwhile, Mary decides to enlist in the Women’s Motor Corps of America as an ambulance driver—and well…fate finds a way.

This film initially caught my attention on two factors: 1) it was just barely before All Quiet at the Western Front in the US (and completed two years prior), and I was curious on its portrayal of the War—would it condemn it or glamorize it, in its retrospective approach?; and 2) as a silent film (sans the music cues and SEX added in the 2012 restoration by Paramount), it mostly relies pretty much solely the expressions and body language of the actors alongside the cinematography to tell its story, as you can’t just type out every little line of the script on title cards and call it a day. Considering how much we have read in class from the POVs of characters who have mostly internalized everything to the point of coming off as notably detached, could the exaggerated and expressive style that is practically necessary for silent films work in a film about the Great War? Thankfully, both of these questions were answered in a way that I felt was satisfying.

Right off the bat, the cinematography is nothing to scoff at: even a shot as simple as David and Sylvie lazily swinging in a hammock together is poignant as the camera literally swings along with them, back and forth, before the sudden arrival of an excited Jack literally jolts their idyllic scene to an abrupt halt. Likewise, there’s an equally stunning dolly zoom later on in the film in which we glide past all the gleeful patrons of a French nightclub drinking and petting before we land on a happy and shamelessly intoxicated Jack. However, the moments that will surely stand out—even in the somewhat drag of a first act—are the aviation and dogfighting scenes, among the first of their kind, and just as enthralling today as they were almost a hundred years ago. Additionally, there are little animations added here and there such as the bubbles that occupy Jack’s hazy mind during his drunk stint on leave in Paris halfway through the film, as well as in the title cards, that are a nice touch.

Many of the texts we’ve read have emphasized the dangers of individuality and how people were stripped of it during the War—here, we have a clearly defined protagonist in the primary POV character, naive Jack Powell. Moreover, the film early on, almost takes on the jovial, patriotic tone that one would more likely see on propaganda posters than on the actual Front; much lime we have a clearly defined “hero”, we have our established villain: German ace pilot Count von Kellermann and his dreaded “Flying Circus” who, among ominous closes ups of the Iron Crosses on their black planes and shots of the pilots giggling and twirling their mustaches as they bomb compounds with glee, are accompanied by a score that seems more suitable for a Star Wars villain. Likewise, the emphasis on comradery amongst the Allied forces is paramount—the British soldiers gleefully rescue Jack went he’s down and cornered by German gunfire, eagerly ushering him into their trench with wide smiles on their faces—”chivalry of the knights of air”, the movie calls it. There’s even a comic relief character, a Dutchman named Herman Schwimpf, whose entire schtick is that he is blissfully and shamelessly patriotic to the point of getting an American flag tattooed on his bicep to wave as his superiors continuously try and fail to literally knock sense into him.

Yet, despite the somewhat light tone starting out, there are notable undercurrents of things not being so great about the Great War: kicking off with the almost immediate and senseless death of Jack and David’s would-be tentmate, Cadet White, before we even have the chance to get attached. Likewise, a fairly comedic scene of Jack’s fun drunk antics in Paris and Mary’s attempts to get him to leave with her to get him back to his post (and away from the French girl he’s been cozy with) is under the threat of him being court martialed, and ends with the painful double whammy of Mary both realizing Jack is in love with Sylvia and then being fired from her job when military police catch her undressing from a gown she used to infiltrate the nightclub, and assume the worst.

It all goes downhill following her abrupt exit, as we are thrown headfirst into the War again with scenes that are, while not very explicitly bloody, are just as intense—from a random soldier getting struck down with shrapnel from a bombing in the Front, to another soldier being crushed by a falling tank, its made abundantly clear that this film, while a romance, is anything but romantic down to its roots. When Jack and David’s relationship gets tested following a misunderstanding, and David is later shot down by the enemy in the following dogfight, Jack makes it a point to brand himself the hero and avenge his fallen friend by taking down as many Germans as he can. Little does he know, David is still alive in German territory, and manages to escape by stealing a German plane. Oh, oh no…

Jack’s stint at heroism ends with a sharp role reversal as he is given tube villainous music cues as he tries to chase and strike down David, believing he’s “only another foe to be slaughtered without mercy”. When he eventually succeeds, he’s finally broken when he realizes his fatal mistake, much like Paul and the French soldier, only this time, he has a grieving family he has to go back to. Rogers and Arlen’s acting in this scene is excellent, and we even cross that blurred line of the friend, brother, and the lover so common in the bonds between soldiers at the time, leading up to arguably the most famed scene of the film nowadays: Jack passionately kissing David on the lips as the latter dies in his arms. And although Jack goes home a celebrated “hero” (to the point of literally having his name and face plastered on newspapers that laud him as such) and is publically showered with adoration and flowery parade rides through town, there’s a distinct emptiness as he looks at the little bear charm David left behind—the one Jack promised to return to his mother. Furthermore, the ending scene between Jack and David’s mother makes the message obvious: “I—I wanted to hate you, John, but I can’t. It wasn’t your fault. It was—war!”

Overall, I really enjoyed this film despite its slow start, and would recommend it even if you don’t like silent films. The acting and the action is excellent, and it really feels like gradually watching characters like Paul get to the point of where they were in their story fresh from their idealistic beginnings—under a less overly violent, nihilistic lens. I can see why this won the Academy Award for Best Picture. My only real complaint is that Mary did NOT deserve Jack—at all.

“All Quaint on the Western Front”, a brief tale of What Could’ve Been; starring Evadne Price

When reading Not So Quiet, there are notable similarities between this text and All Quiet on the Western Front—as we’ve discussed quite a few in class such as the characterization of The “Bitch” Commandment and Himmelstoss as abusive people in power, societal pressures being a factor in driving the POV characters to enlist, and the similar writing style, among other similarities (“I am afraid I am going mad” (P. 101 of my edition) a line that follows the shock of a sudden tragedy where a character dies in the POV character’s arms, and the final ending paragraph are the moments that stood out the most to me while reading Not So Quiet).

Looking further into the history of the author, Evadne Price, I found out that this novel was originally commissioned as a far more blatant rip of All Quiet… following the international success of the latter novel. According to an article by Lucy Scholes of The Paris Review, Price was approached by London-based publisher, Albert E. Marriott, and asked to “write a spoof response about women in the war. He had in mind a title—“All Quaint on The Western Front“—and a pen name for her, Erica Remarks” (emphasis is mine). However, after reading All Quiet herself for the first time, Price felt, understandably so, that making light of such a serious and tragic subject was…y’know, absolutely horrible and insulting (quote from Price herself during an interview with Hazel De Berg: “Anybody who writes a skit on this book wants their brains dusted” (2, around the 14:01 mark). Since Price was never actually a part of the war effort herself,pressed for cash and under the suggestion (and pressure) of Marriott, she decided to base the experiences of the fictional Helen Z. Smith on the borrowed diary entries of former front-line ambulance driver, Winifred Constance Young, who Price had met at the request of a friend. Sadly, Price wasn’t properly compensated for her work by Marriott as detailed in her contract, leading to quite the interesting scandal between the two of them following the successful publication of Not So Quiet among…other hijinks Marriott had gotten up to during that time.

Another interesting detail I found out was that this was actually the first in a series of novels: Not So Quiet was followed by Women of Aftermath in 1931, Shadow Women in 1932, Luxury Ladies in 1933, and They Lived With Me in 1934. These weren’t nearly as successful as Not So Quiet, and I can’t seem to find much information on these books outside of a very brief summary of Women of Aftermath on Goodreads: “A sequel to “Not So Quiet…”. After the war a wife is beaten by her wounded soldier husband” (4). Sadly, they appear to be just as lost as her beloved children’s series Jane Turpin, and like that series, may have gone out of print following their lackluster returns by an audience now gearing up for WWII—the novelty of these types of books seems to have worn off rather quickly during the time, and, according to a paper given at the Marginalized Mainstream conference in 2014 (recorded by the blog Great War Fiction), even Not So Quiet was itself nearly lost before it was rediscovered and reprinted in 1989 by Jane Marcus and Feminist Press respectively (3).

Knowing all of this, how does this information on the behind-the-scenes of Not So Quiet impact your reading of Price’s novel? Does the knowledge of the fact it was initially conceived by as a parody by a man who wanted to cash in on All Quiet’s success change how you read both stories back-to-back as we have in class? How do you think the book would’ve been perceived by audiences of the time (let alone today) if Price had followed through with the parody nature that had been pitched to her—and do any elements of parody still show up in the novel regardless of its shift in direction early on? Are there anymore similarities between these books that we can now point to knowing this context? How does the knowledge that there were sequels to this novel still published under the Helena Zenna Smith pseudonym (and thus, presumably, continued to follow the life of the Smithy character) impact the ending for you guys—does this knowledge cheapen the impact of that final paragraph or does it make it more potent? Finally, how many of you guys wish that there was some kind of biopic about Evadne Price?; because my lord, was this woman quite a fascinating character in of herself.

Sources used in this post:

https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2019/03/29/re-covered-not-so-quietstepdaughters-of-war/ (1)

//nla.org.au/nla.obj-22278695/listen/2-592 (2)

https://greatwarfiction.wordpress.org/helen-zenna-smith-and-the-disguises-of-evadne-price/ (3)

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/18070839-women-of-the-aftermath (4)